Soft Thoughts Ongoing

Over the past year, as part of my research with Arts University Plymouth, I’ve been pulling threads between my background in graphic design, my printmaking practice with Colossal, and this strange new abundance opened up by AI tools. I keep circling back to the question:

What can we learn from traditional graphic design techniques like cut-and-paste, so deeply rooted in Dada and montage, and how do those insights help us navigate the digital revolution we’re in now?

Collage as a practice was born out of scarcity. Hannah Höch, Tristan Tzara, and the Dadaists worked with fragments. Snippets of type, discarded magazines, found photographs. Each fragment carried its own history, a trace of where it came from, and together they made something new. The work wasn’t just about assembly, but about tension: what was left out, what was obscured, what was violently cut.

That scarcity demanded resistance. It created friction. And friction is often where meaning happens.

AI, by contrast, throws me into abundance. Instead of the question What can I find?, it becomes What do I choose to keep out? There is no hunt, no tactile edge, no struggle with the limited pool of material. I find myself moving from scavenger-maker to editor-curator. Is this a fundamental shift in the creative process?

Part of me is excited. I’m curious about the unexpected juxtapositions AI can generate, the distortions and unpredictability that might push me to think differently. But I’m also unsettled. Does the abundance of AI collapse context? When the machine generates rather than sources, what happens to authorship? Where does originality sit?

With Colossal, my mobile print studio, I’ve always grafted the feature of mobility onto printmaking, disrupting fixed spaces, making work on beaches, schools, and streets. It resists passivity. It requires sweat, weight, and labour. That physicality matters to me. I don’t want to lose it as I step into experiments with AI.

So I’m asking: how can I impose new forms of tactility in this digital excess? How do I reclaim constraint, create friction, and build resistance into my processes? Derrida reminds me that meaning lives between chaos and structure. Maybe that’s the space I need to keep working in, testing, iterating, letting uncertainty be a method rather than a problem.

This research isn’t just about my own practice. It’s about teaching, too. How do I articulate these experiments with collage, AI, and post-digital practice to students? How can they help us think differently about authorship, originality, and labour? I’ve already got notes pinned against seminars, crits, residencies, and workshops. The questions feel alive and relevant, especially as higher education grapples with attention, digital fatigue, and the need for inclusive and embodied learning.

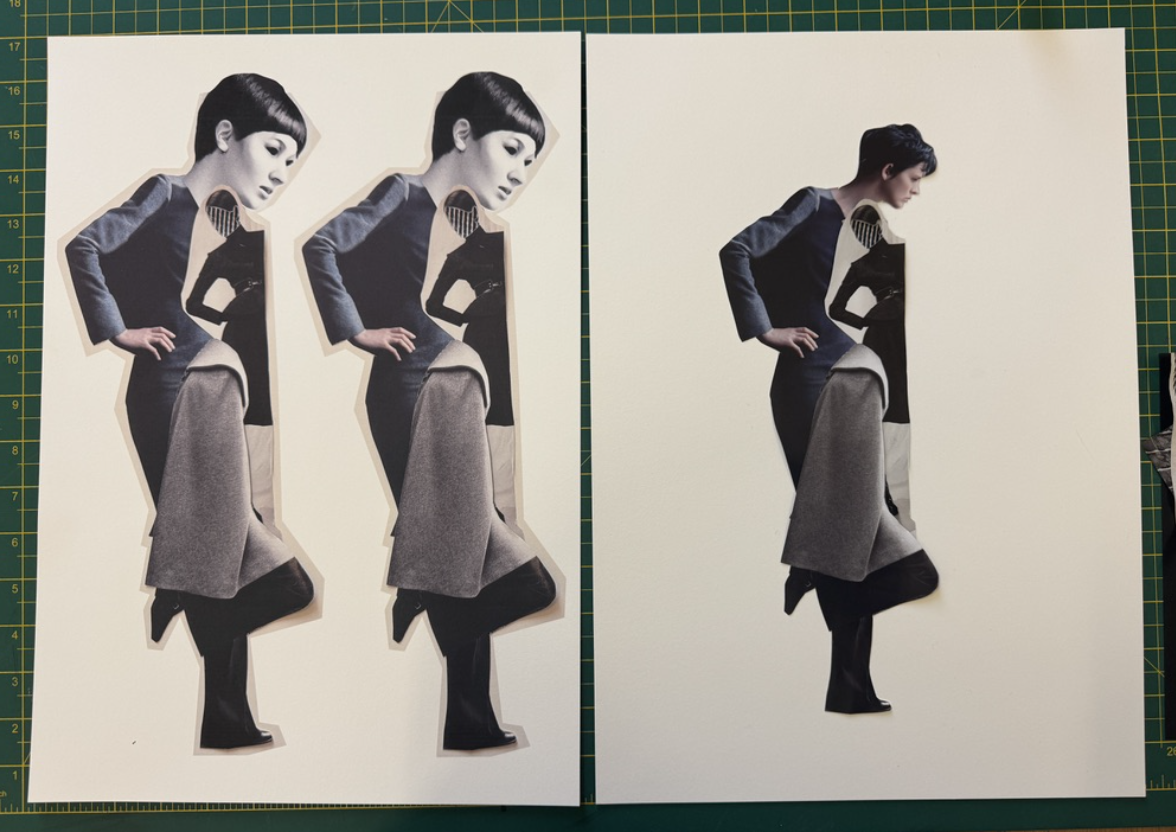

Sue Lewry, AI intervention Collage and Traditional Collage original

Next steps for me are about building tests into my research, workshops that lean into chance and chaos, experimenting with scarcity and abundance side by side, and seeing what happens when I frame AI not as a tool of endless supply but as a collaborator in constraint.

I don’t know yet what I’ll find. But that’s the point. For now, I’m holding onto the curiosity.